Art in Islamic civilization

Main Elements of Islamic Art

Islamic Painting

Islamic Decoration

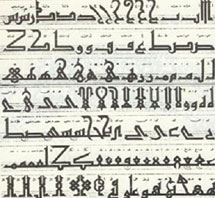

Calligraphic Scripts

History of Islamic Art

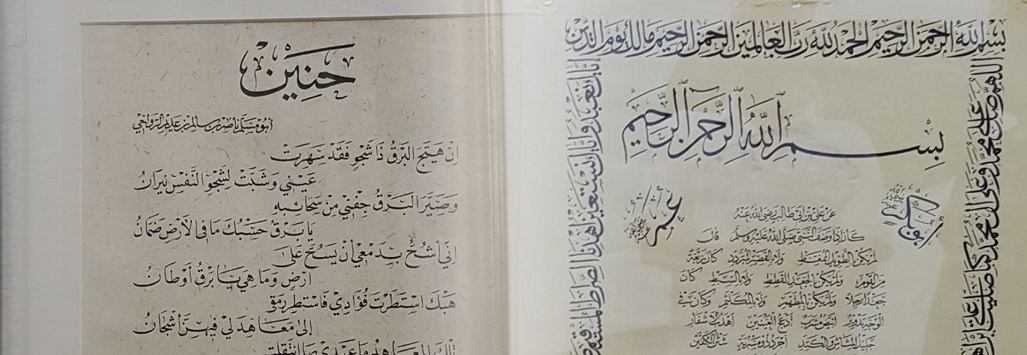

Calligraphy Art

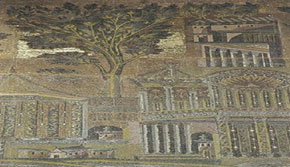

Vegetal and Floral art

Geometrical Art

Calligraphy

References

The phrase “Islamic art” is an umbrella term for post-7th century visual arts, created by Muslim and non-Muslim artists within the territories occupied by the people and cultures of Islam. It embraces art forms such as architecture, architectural decoration, ceramic art, faience mosaics, lustre-ware, relief sculpture, wood and ivory carving, friezes, drawing, painting, calligraphy, book-gilding, manuscript illumination, lacquer-painted bookbinding, textile design, metalworking, goldsmithery, gemstone carving, among others. Historically, Islamic art has developed a wide variety of different sources. It includes elements Greek and early Christian art which it combines with the great Middle Eastern cultures of Egypt, Byzantium, and ancient Persia, along with far eastern cultures of India and China.

Main Elements of Islamic Art

Islamic Art is not the art of a particular country or a particular people. It is the art of a civilization formed by a combination of historical circumstances; the conquest of the Ancient World by the Arabs, the inforced unification of a vast territory under the banner of Islam, a territory which was in turn invaded by various groups of alien peoples. From the start, the direction of Islamic Art was largely determined by political structures which cut across geographical and sociological boundaries.

The complex nature of Islamic Art developed on the basis of Pre-Islamic traditions in the various countries conquered, and a closely integrated blend of Arab, Turkish and Persian traditions brought together in all parts of the new Muslim/Moslem Empire.

The primary fine arts of Islamic civilization are painting (which centers on calligraphy and arabesques) and architecture.

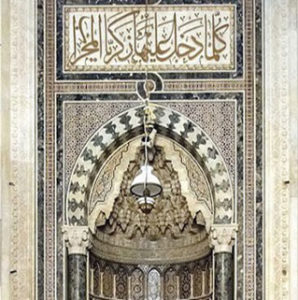

The principal form of Islamic architecture is the mosque. Other great Islamic buildings, both secular (e.g. palaces) and religious (e.g. shrines, religious schools, mausoleums), comprise adaptations of the mosque aesthetic. A classic feature of Islamic architecture is the horseshoe arch.

The central component of the mosque is the prayer hall, where religious service is conducted. The prayer hall, traditionally covered with a great dome (which may be flanked with smaller domes), contains the minbar (a lectern from which sermons are delivered) and mihrab (a niche that indicates the direction of Mecca, toward which Muslims direct their prayers). (A lectern is an elevated desk, typically used to hold a document for public recitation.)

The central component of the mosque is the prayer hall, where religious service is conducted. The prayer hall, traditionally covered with a great dome (which may be flanked with smaller domes), contains the minbar (a lectern from which sermons are delivered) and mihrab (a niche that indicates the direction of Mecca, toward which Muslims direct their prayers). (A lectern is an elevated desk, typically used to hold a document for public recitation.)

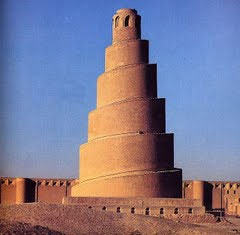

Another common feature is the minaret: a narrow tower with a balcony from which (traditionally) the call to prayer is sounded five times a day. Minarets are often attached to the prayer hall, or positioned around the edges of an arcaded courtyard, itself joined to the prayer hall on one side. In addition to the prayer hall and minarets, the mosque layout may be embellished with additional rooms or buildings.

Islamic Painting

Given that Islamic civilization has traditionally prohibited the depiction of figures in visual art, Islamic painters concentrated their efforts on calligraphy and intricate patterns. The latter may be purely abstract, or may feature floral elements.The term arabesque, meaning “intricate pattern“, springs from the predominance of such patterns in Islamic art.

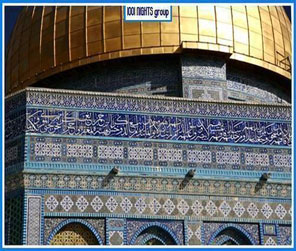

Calligraphy and arabesques are found in abundance upon Islamic architecture (e.g. painted ceramic tiles, mosaics, tracery) and decorative art (e.g. ceramics, metalwork, textiles).

The prohibition of figures in Islamic visual art has generally been strictly enforced, with one major exception: manuscript illumination. In stark contrast to the abstraction of most Islamic visual art, the pages of many Islamic manuscripts feature lush representations of the physical world, including human figures. The scope of Islamic illumination was limited in two ways, however: only secular subjects (with rare exceptions) were treated, and illumination only flourished in the Persianate branch of the Islamic world.

Islamic illumination is clearly rooted in the civilization’s long tradition of flat patterns. Figures (and their physical environments) are not rendered in a realistic, three-dimensional manner, but rather as outlined areas of flat colour. A typical scene is filled with many pattern-covered areas, such as clothing, architectural surfaces, and foliage.

Islamic Decoration

Two important elements in Islamic decorative art are: Floral Patterns and Calligraphy.

– Floral Patterns in Islamic Decoration:

Islamic artists habitually employed flowers and trees as decorative motifs for the embellishment of cloth, objects, personal items and buildings. Their designs were inspired by international as well as local techniques. For instance, Mughal architectural decoration was inspired by European botanical artists, as well as by traditional Persian and Indian flora. A highly ornate as well as intricate art form, floral designs were often used as the basis for “infinite pattern” type decoration, using arabesques (geometricized vegetal patterns) and covering an entire surface. The infinite rhythms conveyed by the repetition of curved lines, produces a relaxing, calming effect, which can be modified and enhanced by variations of line, colour and texture. Sometimes the ornate would be emphasized, and floral designs would be applied to tablets or panels of white marble, in the form of rows of plants finely carved in low relief, along with multi-coloured inlays of precious stones.

– Calligraphy in Islamic Decoration:

Apart the naturalistic, semi-naturalistic and abstract geometrical forms used in the infinite pattern, Arabic calligraphy played a dominant role in Islamic Art and was integrated into every sort of decorative scheme – not least because it provides a link between the language of Muslims and the religion of Islam, as outlined in the Koran/Qur´an. Proverbs and complete passages the Qur´an are still major sources for Islamic calligraphic art and decoration.

Thus, almost all Islamic buildings exhibit some type of inscription in their stone, stucco, marble or mosaic surfaces. The inscription is often, though not always, a quotation the Qur´an. Or single words like “Allah” or “Mohammed” might be repeated many times over the entire surface of the walls. Calligraphic inscriptions are closely associated with the geometry of the building and are frequently employed as a frame around the main architectural elements such as portals and cornices. Sometimes a religious text is confined to a single panel or carved tablet (cartouche) which might be pierced thus creating a specific pattern of light.

Calligraphic Scripts

There are two main scripts in traditional Islamic Calligraphy, the angular Kufic and the cursive Naskhi.

Kufic, the earliest form, which is alledged to have been invented at Kufa, south of Baghdad, accentuates the vertical strokes of the characters. It was used extensively during the first five centuries of Islam in architecture, for copies of the Koran (Qur´an), textiles and pottery. There are eight different types of Kufic script out of which only three are mentioned here: (a) simple Kufic; (b) foliated Kufic which appeared in Egypt during the 9th Century BCE and has the vertical strokes ending in lobed leaves or half-palmettes; (c) floriated Kufic in which floral motiffs and scrolls are added to the leaves and half-palmettes. This seems also to have been developed in Egypt during the 9th Century BCE and reached it´s highest development there under the Fatimids (969-1171).

From the 11th century onward the Naskhi script gradually replaced Kufic. Though a kind of cursive style was already known in the 7th Century BCE, the invention of Naskhi is attributed to Ibn Muqula. Ibn Muqula lived in Baghdad during the 10th century and is also responsible for the development of another type of cursive writing; the thuluth, or thulth. This closely follows Naskhi, but certain elements, like vertical strokes or horizontal lines are exaggerated.

In Iran several cursive styles were invented and developed among which “taliq” was important. Out of “taliq” developed “Nastaliq“, which is a more beautiful, elegant and cursive form of writing. It´s inventor was “Mir Ali Tabrizi“, who was active in the second half of the 14th century. Nastaliq became the predominate style of Persian Calligraphy during the 15th and 16th centuries.

Another important aspect of Islamic Art, generally completely unknown, is it´s rich pictorial and iconographical tradition. The misconception that Islam was an iconaclastic or anti-image culture and that the representation of human beings or living creatures in general was prohibited, is still deeply rooted although the existence of figuative painting in Iran has been recognized now for almost half a century. There is no prohibition against the painting of pictures or the representation of living forms in Islam and there is no mention of it in the Koran (Qur´an).

Certain pronouncements attributed to the Prophet and carried in the Hadith (the collection of traditional sayings of the Prophet) have perhaps been interpreted as prohibition against artistic activity, although they are of purely religious significance. Whatever the reason, the fact remains that in practically no period of Islamic culture were figurative representation and painting suppressed, with the singular exception of the strictly religious sphere where idolatry was feared. Mosques and mausoleums are therefore without figurative representation. Elsewhere, imagery forms one of the most important elements and a multitude of other pictorial traditions were also assimilated during the long and complex history of Islamic Art.

That said, it is fair to say that other experts in Islamic art take a slightly narrower view. According to this view, because the creation of living things like humans and animals is regarded as being the role of God, Islam rightly discourages Islamic painters and sculptors producing such figures. Although it is true that some figurative art can be seen in the Islamic world, it is mostly confined to the decoration of objects and secular buildings and the creation of miniature paintings. See also Mosaic Art.

History of Islamic Art

– Umayyad Art (661-750):

Noted for its religious and civic architecture, such as The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem (built by Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, 691) and the (Umayyad) Great Mosque of Damascus (finished 715).

– Abbasid Art (750-1258):

The Abbasid dynasty shifted the capital Damascus to Baghdad – founded by al-Mansur in 762, the first major city entirely built by Muslims. The city became the new Islamic hub and symbolized the convergence of Eastern and Western art forms: Eastern inspiration Iran, the Eurasian steppes, India and China; Western influence Classical Antiquity and Byzantine Europe. Later, Samarra took over as the capital.

Abbasid architecture was noted for the desert Fortress of Al-Ukhaidir (c.775) 120 miles south of Baghdad, the Great Mosque of Samarra, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo, Abu Dalaf in Iraq, the Great Mosque in Tunis, and the Great Mosque in Kairouan, Tunisia.

Other arts developed under the Abbasids included, textile silk art, wall painting and ancient pottery, notably the invention of lustre-ware (painting on the surface of the glaze with a metallic pigment or lustre). The latter technique was unique to Baghdad potters and ceramicists. Also, calligraphic decorations first began to appear on pottery during this period.

– Umayyad Art in Spain:

Parallel with the Abbasids in Iraq, descendants of the earlier Umayyad dynasty ruled Spain, with Cordoba becoming the second most important cultural centre of the Muslim world after Bagdad. Umayyad art and architecture in Spain was exemplified by the creation of the Great mosque of Cordoba. In particular, this region was noted for its fusion of classical Roman and Islamic architectural designs, and the general development of a Hispano-Islamic idiom in painting, relief sculpture, metal sculpture in the round, and decorative arts like ceramics.

– Fatimid Art in Egypt (909-1171):

Under the Fatimids, Egypt took the lead in the cultural life of western Islam. In the arts, this dynasty was noted for architectural structures like the al-Azhar Mosque and the al-Hakim Mosque of Cairo; ceramic art in the form of pottery decorated with figurative painting and ivory carving as well as relief sculpture and the emergence of the “infinite pattern” of abstract ornamentation. Fatimid art is particularly famous for applying designs to every kind of surface.

– Seljuk Art in Iran and Anatolia (Turkey):

The struggle for power in Iran and the north of India, involving the Tahirids, Samanids, and Ghaznavids, was won by the Seljuk in the middle of the 11th century. In Islamic art, this dynasty was noted above all for its architecture and building designs, exemplified by the Masjid-i Jami in Isfahan, built by Malik Shah.

Fundamental forms of architectural design are developed and permanently formulated for later periods. The most important were the court mosque and the madrasah, as well as forms for tomb towers and mausoleums. Figurative representation, along the lines of a Central Asian iconography, was also greatly expanded across the visual arts. The Seljuks also excelled at stone-carving, used in architectural ornamentation, as well as painted tiles and faience mosaics.

– Mamluk Art in Syria and Egypt (1250-1517):

Many monumental stone works of Islamic architecture were created during this period include the Madrasah-Mausoleum of Sultan Hasan, Cairo (1356-63), the Madrasah-Mausoleum of Sultan Kalaun, Cairo (1284-5), and Kayt Bey´s Madrasah-Mausoleum (c.1460-70). Exteriors as well as interiors became richly decorated in a variety of media – plaster, relief carving, and decorative painting. Enameled glass and metalwork were also greatly developed (c.1250-1400). For example, the superb metal basin of Mamluk silver metalwork known as the “Baptistere de Saint Louis” (Syria, 1290-1310), is one of the greatest masterpieces of its type in Islamic art. Decorated on the outside with a central frieze of figures and two corresponding friezes of animals, it is also ornamented with elaborate hunting scenes on the inside. In general the Mamluk era is remembered as the golden age of medieval near Eastern Islamic culture.

Many monumental stone works of Islamic architecture were created during this period include the Madrasah-Mausoleum of Sultan Hasan, Cairo (1356-63), the Madrasah-Mausoleum of Sultan Kalaun, Cairo (1284-5), and Kayt Bey´s Madrasah-Mausoleum (c.1460-70). Exteriors as well as interiors became richly decorated in a variety of media – plaster, relief carving, and decorative painting. Enameled glass and metalwork were also greatly developed (c.1250-1400). For example, the superb metal basin of Mamluk silver metalwork known as the “Baptistere de Saint Louis” (Syria, 1290-1310), is one of the greatest masterpieces of its type in Islamic art. Decorated on the outside with a central frieze of figures and two corresponding friezes of animals, it is also ornamented with elaborate hunting scenes on the inside. In general the Mamluk era is remembered as the golden age of medieval near Eastern Islamic culture.

– Nasrid Art in Spain (1232-1492):

The Nasrid dynasty, centred on their court in Granada, created a culture that attained a level of magnificence without parallel in Muslim Spain, recreating the glories of the first great Islamic period under Umayyad rule. Nasrid architecture led the way, exemplified by the Alhambra Palace in Granada . In this building the fundamental elements of Islamic architecture and architectural design found their highest expression: for instance, the illusion of a building floating above ground. In decorative art, lustre-painting was greatly developed, as was textile weaving in gold brocade and embroidery.

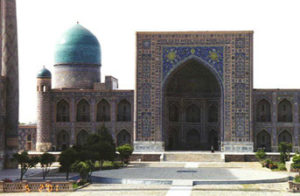

– Timurid Period (c.1360-1500):

Mongol rule in Iran was succeeded by that of Timur (Tamerlane) who came south of Samarkand. Timurid architecture is exemplified by the mosques of Kernan and Yezd , the Great Mosque of Samarkand (Bibi Khanum mosque) begun around 1400, the Gur-i Amir, Timur´s mausoleum in Samarkand (1405), and the Blue Mosque in Tabriz (1465). Architectural decoration employed polychrome faience to the greatest effect. In the other visual arts, Timurid painting introduced the concept of using the entire pictorial area, while illuminated manuscripts were produced in the “Imperial Timurid style“. Notable schools of Timurid painting sprang up in Shiraz, Herat and elsewhere. Herat produced a series of magnificent painted manuscripts, as well as a corresponding set of developments in the Islamic arts of calligraphy and book-binding. Stained glass art was also developed. In general, Timurid art may be seen as a refinement, even sublimation, of the basic ideals of eastern Islamic art.

Mongol rule in Iran was succeeded by that of Timur (Tamerlane) who came south of Samarkand. Timurid architecture is exemplified by the mosques of Kernan and Yezd , the Great Mosque of Samarkand (Bibi Khanum mosque) begun around 1400, the Gur-i Amir, Timur´s mausoleum in Samarkand (1405), and the Blue Mosque in Tabriz (1465). Architectural decoration employed polychrome faience to the greatest effect. In the other visual arts, Timurid painting introduced the concept of using the entire pictorial area, while illuminated manuscripts were produced in the “Imperial Timurid style“. Notable schools of Timurid painting sprang up in Shiraz, Herat and elsewhere. Herat produced a series of magnificent painted manuscripts, as well as a corresponding set of developments in the Islamic arts of calligraphy and book-binding. Stained glass art was also developed. In general, Timurid art may be seen as a refinement, even sublimation, of the basic ideals of eastern Islamic art.

– Ottoman Art (c.1400-1900):

With the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, once the centre of Byzantium and the Eastern Roman Empire, the city once again became a focal point for western Islamic art and culture. Ottoman architecture is noted above all for the domed mosque. An early form was the Ulu Cami mosque, Bursa ; later Ottoman buildings by Islamic architects include: the Sulaymaniyeh Cami Mosque of Sultan Sulayman (begun 1550) and the Selimiyeh Cami mosque, Edirne (1567-74) – both designed by Sinan, the most celebrated of all Ottoman architects – the mosque of Sultan Ahmet I (known as “the Blue Mosque“) (1603-17), and the Sultan Ahmet Cami mosque (1609-16).

Advances in architectural decoration included a new style of floral polychrome designs in ceramic tilework and pottery (plus the discovery of the bright red pigment used in ceramics, known as Iznik red), while in painting, Ottoman artists developed a new canon of colour, composition and iconography. One of the most famous of Ottoman crafts was the knotted rug, which – in its use, form and decoration – embodied most of the salient elements of Muslim culture. Also, Ottoman calligraphers developed Diwani script, a new cursive style of Arabic calligraphy. Invented by Housam Roumi, it became highly popular under Suleyman I the Magnificent (1520–66).

Advances in architectural decoration included a new style of floral polychrome designs in ceramic tilework and pottery (plus the discovery of the bright red pigment used in ceramics, known as Iznik red), while in painting, Ottoman artists developed a new canon of colour, composition and iconography. One of the most famous of Ottoman crafts was the knotted rug, which – in its use, form and decoration – embodied most of the salient elements of Muslim culture. Also, Ottoman calligraphers developed Diwani script, a new cursive style of Arabic calligraphy. Invented by Housam Roumi, it became highly popular under Suleyman I the Magnificent (1520–66).

In general, an important aspect of Ottoman art is its play on contrasts: between tectonic qualities and the dissolution of materials, between realistic forms with fine detail and “infinite pattern” abstraction.

The architecture of the Ottomans, especially after the early formative period, is primarily built of stone. Ottoman architecture in fact is known for the very high quality of its masonry. Still, combinations of brick and stone are very common, and brick is used for arches, domes and vaults. Lead is used to cover domes and minaret caps, especially from the 10th / 16th century onwards. Polychrome glazed ceramic tiles, such as the renowned Iznik tiles in which white and blue dominate, are used extensively as wall coverings, and by the 10th / 16th century often replace marble as a sheathing material. Wood is used both as a structural and as a decorative material, and it is the predominant material for the houses of the Ottoman capital, Istanbul.

Calligraphy Art:

In the Islamic world, Arabic calligraphy has been used to a much greater extent and in astonishingly varied and imaginative ways, which have taken the written word far beyond pen and paper into all art forms and materials. For these reasons, calligraphy may be counted as a uniquely original feature of Islamic art. The genius of Islamic calligraphy lies not only in the endless creativity and versatility, but also in the balance struck by calligraphers between transmitting a text and expressing its meaning through a formal aesthetic code.

In general, calligraphic inscriptions on works of art comprise one or more of the following types of text:

- Qu’ranic quotations

- other religious texts

- poems

- praise for rulers

- aphorisms

Arabic calligraphy, geometric patterns, and the vegetal motif – provide the basic building blocks for an extensive history and collection of Muslim art which appears in architecture, book copying and binding, tapestries, glassware, ceramics, metalwork, woodwork and the entire range of decorative arts.

Moreover, Islamic art is iconoclastic, especially in the mosque and other religious spaces – that is, there is no art that contains the human figure.

Vegetal and Floral art:

Although, Muslim art was not, of course, developed independently of influences from nature and the environment, their representation was abstract rather than realistic, as in Western art. This is seen clearly in vegetal forms where plant branches, leaves, and flowers were woven and interlaced into and often not distinguished, from the geometrical lines around them as seen in the arabesque. The use of vegetal forms in Islamic art is also conditioned to some extent by the Islamic prohibition of the imitation of living creatures. However, this interdiction naturally decreases with the descent from human to animal to vegetable forms. Art critics describe the floral depictions and ornaments of the artists of Islam as conventional; lacking the effects of growth and the creation of life (Dobree 1920). In their opinion, the reason behind the absence of growth was due to the natural environment of the Muslim countries, where the experience of spring, the season of plant growth is fleeting. However, the religious prohibition was behind the absence of lifelike creation in much of the Islamic floral art.

The Muslims used foliage with great delicacy especially around the arches and windows. The stucco borders used in the mausoleum of the Ayyubid Sultan Qalawun, built in Cairo (Egypt) in 1284/85, consisted of buds and leaves arranged in a continuous scroll pattern. The mausoleum also contained examples of other floral illustrations set in rectangular and circular panels, a feature which became particularly popular in the 15th century (Poole, 1886). The use of this type of art extended to many ornamental objects, such as pottery, and wood and leather carving as well as coloured tiles.

Geometrical Art:

The second element of Islamic art involves geometrical patterns. The artists used and developed geometrical art for two main reasons. The first reason is that it provided an alternative to the prohibited depiction of living creatures. Abstract geometrical forms were particularly favoured in mosques because they encourage spiritual contemplation, in contrast to portrayals of living creatures, which divert attention to the desires of creatures rather than the will of God. Thus geometry became central to the art of the Muslim World, allowing artists to free their imagination and creativity. A new form of art, based wholly on mathematical shapes and forms, such as circles, squares and triangles, emerged.

The second reason for the evolution of geometrical art was the sophistication and popularity of the science of geometry in the Muslim world.

This geometrical art is very much connected to the famous concept of the arabesque, which is defined as “ornamental work used for flat surfaces consisting of interlacing geometrical patterns of polygons, circles, and interlocked lines and curves” The arabesque pattern is composed of many units joined and interlaced together, flowing from each other in all directions. Each unit, although it is independent and complete and can stand alone, forms part of the whole design . The most common use of arabesque is decorative, consisting mainly of a two dimensional pattern, covering surfaces such as ceilings, walls, carpets, furniture, and textiles.

This geometrical art is very much connected to the famous concept of the arabesque, which is defined as “ornamental work used for flat surfaces consisting of interlacing geometrical patterns of polygons, circles, and interlocked lines and curves” The arabesque pattern is composed of many units joined and interlaced together, flowing from each other in all directions. Each unit, although it is independent and complete and can stand alone, forms part of the whole design . The most common use of arabesque is decorative, consisting mainly of a two dimensional pattern, covering surfaces such as ceilings, walls, carpets, furniture, and textiles.

Arabesque can also be floral, using a stalk, leaf, or flower (tawriq) as its artistic medium, or a combination of both floral and geometric patterns. The expression embodied in its interlacing pattern, cohesive movement, gravity, mass, and volume signifies infinity and produces a contemplative feeling in the spectator leading him slowly into the depth of the Divine presence.

It is clearly evident that much of the credit for the development and the popularity of geometrical art goes to the artists of the Islamic world, although its origins are still debated. Claims have been made that primitive geometrical decoration was used in Ancient Egypt as well as in Mesopotamia, Persia, Syria, and India.

Calligraphy:

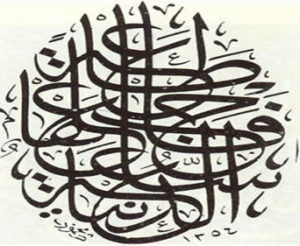

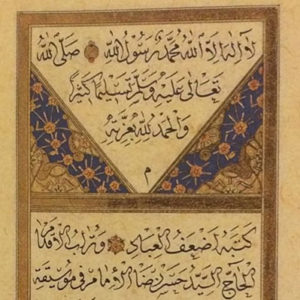

The third decorative form of art developed in Islamic culture was calligraphy, which consists of the use of artistic lettering, sometimes combined with geometrical and natural forms.

The development of calligraphy as a decorative art was due to a number of factors. The first of these is the importance which Muslims attach to their Holy Qur’an, which promises divine blessings to those who read and write it down. “The pen, a symbol of knowledge“.

This indicates that the aim of Islamic calligraphy was not merely to provide decoration but also to worship and remember Allah. The Qur’anic verses mostly used are those which are said in the act of worship , or contain supplications, or describe some of the characters of Allah, or his Prophet Muhammad. Calligraphy is also used on dedication stones to record the foundation of some key Islamic buildings.

Arabic calligraphy was mostly written in two scripts :The first is the Kufic script, whose name is derived from the city of Kufa, where it was invented by scribes engaged in the transcription of the Qur’an who set up a famous school of writing . The letters of this script have a rectangular form, which made them well suited to architectural use. It was used in many early Qur’an manuscripts and for inscriptions, including those at the Dome of the Rock. Confusingly, the same name is also commonly used for a second major group of script styles, which came to prominence in the 10th century. These new, more angular styles came to include many fanciful variants such as foliated Kufic (decorated with curling leaf shapes) and floriated Kufic (decorated with flower forms). This second group of Kufic styles was used in contexts as varied as Qu’ran manuscripts, coinage, architectural inscriptions and the decoration of ceramics.

Arabic calligraphy was mostly written in two scripts :The first is the Kufic script, whose name is derived from the city of Kufa, where it was invented by scribes engaged in the transcription of the Qur’an who set up a famous school of writing . The letters of this script have a rectangular form, which made them well suited to architectural use. It was used in many early Qur’an manuscripts and for inscriptions, including those at the Dome of the Rock. Confusingly, the same name is also commonly used for a second major group of script styles, which came to prominence in the 10th century. These new, more angular styles came to include many fanciful variants such as foliated Kufic (decorated with curling leaf shapes) and floriated Kufic (decorated with flower forms). This second group of Kufic styles was used in contexts as varied as Qu’ran manuscripts, coinage, architectural inscriptions and the decoration of ceramics.

The other script of Arabic calligraphy is known as Naskhi. This style of Arabic writing is older than Kufic, yet it resembles the characters used by modern Arabic writing and printing. It is characterised by a round and cursive shape to its letters. The Naskhi calligraphy became more popular than Kufic and was substantially developed by the Ottomans.

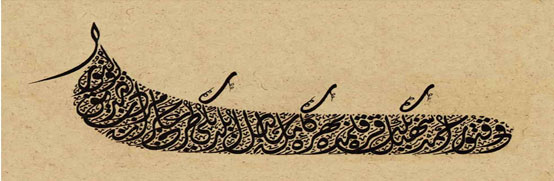

The Muslim artist – some times – to enter more than one line in a single painting, which gave the gift of splendor , and pushed this art to progress and creativity, and the competition was completed and improved, motivated by access to beauty. The artist did not stop in the art of calligraphy at the edge of the character and improve it, but went another step; it made the same letter a decorative material, and turned the paintings of the line to decorative panels, and you marvel at the ability of the Muslim artist to control the painting; the expressive task and decorative task, then make the second task a gilt for the first task. The artist has not only reached the art of calligraphy of creativity, which reached the peak, but turned the letter to the new horizons; where the craft became a tool of art and an effective material proved its ability to give, once the eye is on the painting to find itself – at first sight – In front of a diagnostic drawing of a body (bird – animal – fruit ), if examined, found that the formation was not only words and Arabic characters created by the artist, and often its meaning is closely related to the apparent form, and here lies creativity . Thus, the heritage of Muslims was remarkable in the field of calligraphy, which made it a distinctive art of Islamic civilization throughout its ages, and in every part of the Muslim world.

The Muslim artist – some times – to enter more than one line in a single painting, which gave the gift of splendor , and pushed this art to progress and creativity, and the competition was completed and improved, motivated by access to beauty. The artist did not stop in the art of calligraphy at the edge of the character and improve it, but went another step; it made the same letter a decorative material, and turned the paintings of the line to decorative panels, and you marvel at the ability of the Muslim artist to control the painting; the expressive task and decorative task, then make the second task a gilt for the first task. The artist has not only reached the art of calligraphy of creativity, which reached the peak, but turned the letter to the new horizons; where the craft became a tool of art and an effective material proved its ability to give, once the eye is on the painting to find itself – at first sight – In front of a diagnostic drawing of a body (bird – animal – fruit ), if examined, found that the formation was not only words and Arabic characters created by the artist, and often its meaning is closely related to the apparent form, and here lies creativity . Thus, the heritage of Muslims was remarkable in the field of calligraphy, which made it a distinctive art of Islamic civilization throughout its ages, and in every part of the Muslim world.

– Calligraphy in the Othmanis Era:

Othmani’s calligraphy school is an independent school famed by Arabic Calligraphy, Islamic ornamentation, making Ahar Papers, bindings and drawings. This school played a significant role in developing the Arts and became the inference of all previous cultures such as: the Abbasids, Fatimids, Ayyubids and Seljuqs civilizations. Therefore, scholars and historians called Othmani Era as the Golden Era of Arabic Calligraphy, Calligraphers, during that era, had the respect of Othmani Sultans and consequently received special consideration through entitling them to run the Sultani Courts along with handwriting the Holy Quran, manuscripts and on the walls of mosques.

Nowadays, we can see the fabulous Arabic scripts of Othmani calligraphy’s masters decorating the Othmani’s mosques, palaces and even the graves. Moreover, the Othmani sultans attracted calligraphers from all cities to work in Istanbul, the Capital of Othmani Caliphate, One of the calligraphy’s masters, during the era of Sultan Bayyzeed II, was Sheik Hamd Allah Al-Amasy who was the first mentor (First Imam) for all calligraphers at that time. Then came Al-Hafez Othman, who was titled as the second Imam. He amazingly handwrote the Holy Quran using the Nasik script. Then came Mahmoud Jalal Al-Deen, and the genius innovator Mustafa Raqim, the Chief of Calligraphers at his time, who left a great influence on developing the Jeli Thulth Script, and his style in handwriting this script is still pioneering till now. His style was followed by (Mohammad Sami, Mohammad Nadeef, Aref, Ahmed Kamel, Haqi, Hamid Al-Amidi and Mustafa Haleem).

Furthermore, Othmani calligraphers invented new scripts such as Dewani, Jeli Dewani, Tughra and Ruqqaa. These inventions would have never appeared without the encouragement that such calligraphers found from their Sultans at that time.

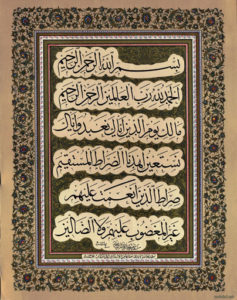

– Nasikh Script:

Is one of the six Arabic Calligraphy Scripts, It was firstly standardized by the Abbasid Minister Ibn Muqla , Then, by the famous Abbasid calligrapher Ibn Al-Bawab and subsequently by the great calligraphy’s master Yagout Al-Mustasemi at the end of Abbasids era. In the beginning of the Othmani Era came Sheik Hamd Allah Al-Amasy who elevated this script to its limitless beauty to become the first founder of this script in the Othmani era. His approach was followed by Al-Hafez Othman, the handwriter of the Holy Quran, Mahmoud Jalal Al-Deen, Mustafa Izzat and Mohammad Shawki. Those calligraphers were the elite Othmani Nasik handwriters.

Is one of the six Arabic Calligraphy Scripts, It was firstly standardized by the Abbasid Minister Ibn Muqla , Then, by the famous Abbasid calligrapher Ibn Al-Bawab and subsequently by the great calligraphy’s master Yagout Al-Mustasemi at the end of Abbasids era. In the beginning of the Othmani Era came Sheik Hamd Allah Al-Amasy who elevated this script to its limitless beauty to become the first founder of this script in the Othmani era. His approach was followed by Al-Hafez Othman, the handwriter of the Holy Quran, Mahmoud Jalal Al-Deen, Mustafa Izzat and Mohammad Shawki. Those calligraphers were the elite Othmani Nasik handwriters.

– Thulth Script:

Is the most well-known Script among the other six Arabic Calligraphy Scripts it was derived from Nasik Script the first calligrapher who standardized the rules of Thulth script was the Abbasid Minister ibn Muqla in the fourth Hijri century.

Is the most well-known Script among the other six Arabic Calligraphy Scripts it was derived from Nasik Script the first calligrapher who standardized the rules of Thulth script was the Abbasid Minister ibn Muqla in the fourth Hijri century.

Then came Yagout Al-Mustasemi who added his significant touches thereto and consequently deserved to be the mentor for all calligraphers in his time. Then came the first Othmani Calligraphy’s Imam (Sheik Hamd Allah Al-Amasy) who established his distinguished approach in handwriting this script to pave the way for other Othmani calligraphers to follow his approach particularly Hafez Othman, Mahmoud Jalal Al-Deen and the genius Mustafa Raqim who also put his touches and established a concrete style followed by all later calligraphers such as: Mustafa Izzat and Abdullah Al-Zuhdi, the handwriter of the two Holy Shrines, and Mohammad Shafiq, the handwriter of the Dome of the Rock.

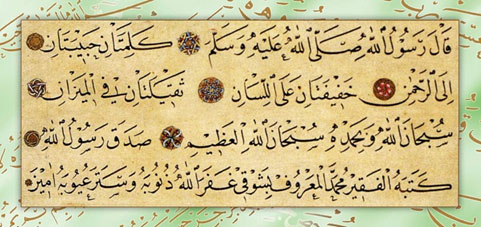

– Ijazza Script (the Signature Script):

Is one of the authenticated Arabic Scripts Its name was taken from the practice of the calligraphy’s masters when they used to grant their certificates (Ijazza) to their students Moreover, Ijazza, in this context, is like the school certificate. It was also called Signature Script to refer to the signee of the certificate or to the one who grants certificates.

Is one of the authenticated Arabic Scripts Its name was taken from the practice of the calligraphy’s masters when they used to grant their certificates (Ijazza) to their students Moreover, Ijazza, in this context, is like the school certificate. It was also called Signature Script to refer to the signee of the certificate or to the one who grants certificates.

This Script was standardized by Yousef Al-Shajari who called it (the Presidential Script) because it was used frequently by Al-Fadel Bin Abbas, the Minister of Abbasid Caliphate (Al-Mamooun). Al-Fadel Bin Abbas was also known as the owner of two presidential positions.

This Script is a mix between Thulth and Nasik scripts. It was developed by Sheik Hamd Allah Al-Amasy, Hafez Othman, Mahmoud Jalal Al-Deen, Mustafa Raqim, Mustafa Izzat, Hassan Rida, Mohammad Shawki and Abdel Aziz Al-Refa’ai.

– Dewani Script:

This script was named to refer to the Sultani, Governmental and Official Courts during the Othmani Caliphate. It was standardized by Ibrahim Muneef, during the Era of Sultan Mohammad Al-Fatih (AKA Mohammad the Conqueror). This script is derived from Taleeq Script. It was developed by the Minister Calligrapher Ahmed Shala Basha and the Othmani calligrapher Mohammad Izzat. Since then, most calligraphers have been following the method of these two calligraphy’s masters in handwriting this script.

This script was named to refer to the Sultani, Governmental and Official Courts during the Othmani Caliphate. It was standardized by Ibrahim Muneef, during the Era of Sultan Mohammad Al-Fatih (AKA Mohammad the Conqueror). This script is derived from Taleeq Script. It was developed by the Minister Calligrapher Ahmed Shala Basha and the Othmani calligrapher Mohammad Izzat. Since then, most calligraphers have been following the method of these two calligraphy’s masters in handwriting this script.

– Jeli Dewani Script:

This script is derived from Taleeq Script. It has the same features and shapes of Dewani script with a distinguished difference in using a lot of decorative marks thereon. This script appeared in the tenth Hijri century and was developed by the Minister Calligrapher Ahmed Shala Basha. It was used by the most famous calligraphers such as: Mohammad Shafiq, Mohammad Izzat, Sami Afandi, Ismail Haqi and Hamid Al-Amidi.

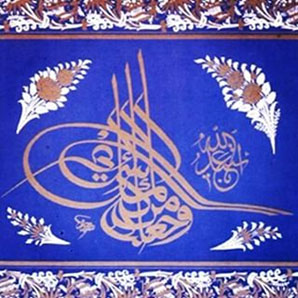

– Tughra Script:

Tughra refers to the signature of the Othmani Sultan placed on the top of sultani decrees. It was first used by Sultan Murad the third. Tughra is a mix between Dewani and Ijazza scripts and could be also used on Islamic coins. It was developed by Mustafa Raqim, Sami Afandi and Ismail Haqi, who also known as Tughraish.

Tughra refers to the signature of the Othmani Sultan placed on the top of sultani decrees. It was first used by Sultan Murad the third. Tughra is a mix between Dewani and Ijazza scripts and could be also used on Islamic coins. It was developed by Mustafa Raqim, Sami Afandi and Ismail Haqi, who also known as Tughraish.

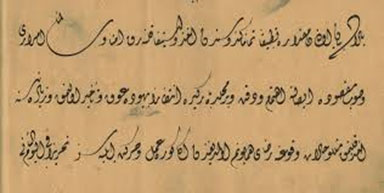

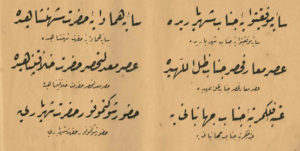

– Ruqqaa Script:

This script is the fastest and the easiest handwritten script. It was used in Sultani Courts and among ordinary people due to its simplicity. Moreover, it was widely used during the Othmani State. It was standardized by Mumtaz Bey, the teacher of calligraphy for the Othmani Sultan Abdel Majeed Khan, 1863. This script was mastered by Mohammad Izzat who also composed a manuscript for different types of Arabic Scripts. Moreover, this manuscript is considered a very valuable reference for Ruqqaa Script.

Arabic calligraphy has reached the height level of perfection and beauty in the Ottoman Empire at the hands of senior masters. The master, Hamed Al-Amadi (1891-1982) was the last calligraphers of Ottomans, where he authorized Mr. Hashim al-Baghdadi, who was the best successor in this great art, and then calligrapher Sheikh Haj Mahdi Al-Jubouri, who authorized Master Yacoub Abu Shawrieh.

He became one of the most famous calligraphers of the era, which is characterized by its unique style, which was witnessed by the Masters of calligraphy