Amedeo Modigliani Biography

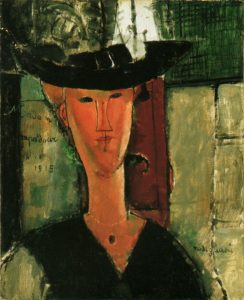

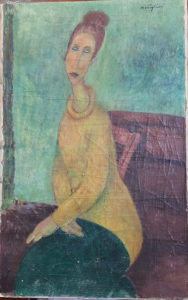

Amedeo Modigliani was an Italian modern artist; a painter and sculptor known for his simplified and elongated forms.

Family and early life

Art student years

Early Literary Influences

Paris

Friends And Influences

The 1917 Paris Show

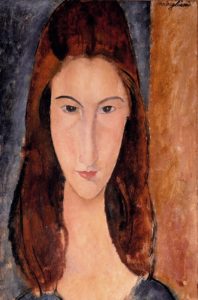

Jeanne Hébuterne

DeathLegacy

Family and early life

Modigliani was born into a Jewish family in Livorno, Italy. A port city, Livorno had long served as a refuge for a lot of people, and was home to a large Jewish community.

Modigliani was born into a Jewish family in Livorno, Italy. A port city, Livorno had long served as a refuge for a lot of people, and was home to a large Jewish community.

His maternal great-great-grandfather, Solomon Garsin, had immigrated to Livorno in the 18th century as a refugee.

Modigliani’s mother (Eugénie Garsin), who was born and grew up in Marseille, was descended from an intellectual, scholarly family of Sephardic Jews, generations of whom had resided along the Mediterranean coastline. Her ancestors were learned people, fluent in many languages, known authorities on sacred Jewish texts, and founders of a school of Talmudic studies. Family legend traced the Garsins’ lineage to the 17th-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza. The family business was believed to be a credit agency with branches in Livorno, Marseille, Tunis, and London. Their financial fortunes ebbed and flowed.

Modigliani’s father, Flaminio, hailed from a family of successful businessmen and entrepreneurs. While not as culturally sophisticated as the Garsins, they knew how to invest in and develop thriving business endeavors. When the Garsin and Modigliani families announced the engagement of their children, Flaminio was a wealthy young mining engineer. He managed the mine in Sardinia and also managed the almost 30,000 acres of timberland the family owned. A reversal in fortune occurred to this prosperous family in 1883. An economic downturn in the price of metal plunged the Modigliani’s into bankruptcy. Ever resourceful, Modigliani’s mother used her social contacts to establish a school and, along with her two sisters, made the school into a successful enterprise.

Modigliani was the fourth child, whose birth coincided with the disastrous financial collapse of his father’s business interests. Amedeo’s birth saved the family from ruin; according to an ancient law, creditors could not seize the bed of a pregnant woman or a mother with a newborn child. The bailiffs entered the family’s home just as Eugenia went into labour the family protected their most valuable assets by piling them on top of her.

Modigliani had a close relationship with his mother, who taught him at home until he was 10 years. Beset with health problems after an attack of pleurisy when he was about 11 years, a few years later he developed a case of typhoid fever. When he was 16 years he was taken ill again and contracted the tuberculosis which would later claim his life. After Modigliani recovered from the second bout of pleurisy, his mother took him on a tour of southern Italy: Naples, Capri, Rome and Amalfi, then north to Florence and Venice.

His mother was, in many ways, instrumental in his ability to pursue art as a vocation. When he was 11 years of age, she had noted in her diary: “The child’s character is still so unformed that I cannot say what I think of it. He behaves like a spoiled child, but he does not lack intelligence. We shall have to wait and see what is inside this chrysalis، perhaps an artist?

Art student years

Modigliani is known to have drawn and painted from a very early age, and thought himself “already a painter”, his mother wrote, even before beginning formal studies. Despite her misgivings that launching him on a course of studying art would impinge upon his other studies, his mother indulged the young Modigliani’s passion for the subject.

At the age of fourteen, while sick with typhoid fever, he raved in his delirium that he wanted, above all else, to see the paintings in the Palazzo Pitti and the Uffizi in Florence. As Livorno’s local museum housed only a sparse few paintings by the Italian Renaissance masters, the tales he had heard about the great works held in Florence intrigued him, and it was a source of considerable despair to him, in his sickened state, that he might never get the chance to view them in person. His mother promised that she would take him to Florence herself, the moment he was recovered. Not only did she fulfil this promise, but she also undertook to enroll him with the best painting master in Livorno, Guglielmo Micheli.

Early literary influences

Modigliani worked in Micheli’s Art School from 1898 to 1900. In 1901, whilst in Rome, Modigliani admired the work of Domenico Morelli, a painter of dramatic religious and literary scenes. Morelli had served as an inspiration for a group of iconoclasts who were known by the title “the Macchiaioli”, and Modigliani had already been exposed to the influences of the Macchiaioli. This localized landscape movement reacted against the bourgeois styling of the academic genre painters. While sympathetically connected to (and actually pre-dating) the French Impressionists, the Macchiaioli did not make the same impact upon international art culture as did the contemporaries and followers of Monet, and are today largely forgotten outside Italy.

Modigliani’s connection with the movement was through Guglielmo Micheli, his first art teacher. Micheli was not only a Macchiaioli himself, but had been a pupil of the famous Giovanni Fattori, a founder of the movement. Micheli’s work, however, was so fashionable and the genre so commonplace that the young Modigliani reacted against it, preferring to ignore the obsession with landscape that, as with French Impressionism, characterized the movement. Micheli also tried to encourage his pupils to paint en plein air, but Modigliani never really got a taste for this style of working, sketching in cafés, but preferring to paint indoors, and especially in his own studio. Even when compelled to paint landscapes (three are known to exist), Modigliani chose a proto-Cubist palette more akin to Paul Cezanne than to the Macchiaioli.

Having been exposed to erudite philosophical literature as a young boy under the tutelage of Isaco Garsin, his maternal grandfather, he continued to read and be influenced through his art studies by the writings of Nietzsche, Baudelaire, Carducci, Comte de Lautréamont, and others, and developed the belief that the only route to true creativity was through defiance and disorder.

Letters that he wrote from his ‘sabbatical’ in Capri in 1901 clearly indicate that he is being more and more influenced by the thinking of Nietzsche. In these letters, he advised friend Oscar Ghiglia; “(hold sacred all) which can exalt and excite your intelligence… (and) … seek to provoke … and to perpetuate … these fertile stimuli, because they can push the intelligence to its maximum creative power.”

The work of Lautréamont was equally influential at this time. This doomed poet’s Les Chants de Maldoror became the seminal work for the Parisian Surrealists of Modigliani’s generation, and the book became Modigliani’s favorite to the extent that he learnt it by heart. The poetry of Lautréamont is characterized by the juxtaposition of fantastical elements, and by sadistic imagery; the fact that Modigliani was so taken by this text in his early teens gives a good indication of his developing tastes. Baudelaire and D’Annunzio similarly appealed to the young artist, with their interest in corrupted beauty, and the expression of that insight through Symbolist imagery.

Modigliani wrote to Ghiglia extensively from Capri, where his mother had taken him to assist in his recovery from tuberculosis. These letters are a sounding board for the developing ideas brewing in Modigliani’s mind. Ghiglia was seven years Modigliani’s senior, and it is likely that it was he who showed the young man the limits of his horizons in Livorno. Like all precocious teenagers, Modigliani preferred the company of older companions, and Ghiglia’s role in his adolescence was to be a sympathetic ear as he worked himself out, principally in the convoluted letters that he regularly sent, and which survive today.

“Dear friend

I write to pour myself out to you and to affirm myself to myself.

I am the prey of great powers that surge forth and then disintegrate…

A bourgeois told me today – insulted me – that I or at least my brain was lazy. It did me good. I should like such a warning every morning upon awakening: but they cannot understand us nor can they understand life…”

Paris

In 1906, Modigliani moved to Paris, then the focal point of the avant-garde. In fact, his arrival at the centre of artistic experimentation coincided with the arrival of two other foreigners who were also to leave their marks upon the art world: Gino Severini and Juan Gris.

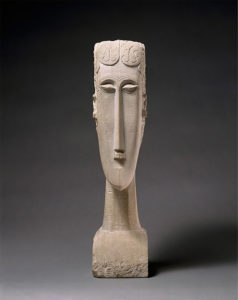

He later befriended Jacob Epstein, they aimed to set up a studio together with a shared vision to create a Temple of Beauty to be enjoyed by all, for which Modigliani created drawings and paintings of the intended stone caryatids for ‘The Pillars of Tenderness ‘which would support the imagined temple.

Modigliani settled in Le Bateau-Lavoir, a commune for penniless artists in Montmartre, renting himself a studio in Rue Caulaincourt. Even though this artists’ quarter of Montmartre was characterized by generalized poverty, Modigliani himself presented – initially, at least – as one would expect the son of a family trying to maintain the appearances of its lost financial standing to present: his wardrobe was dapper without ostentation, and the studio he rented was appointed in a style appropriate to someone with a finely attuned taste in plush drapery and Renaissance reproductions. He soon made efforts to assume the guise of the bohemian artist, but, even in his brown

corduroys, scarlet scarf and large black hat, he continued to appear as if he were slumming it, having fallen upon harder times.

When he first arrived in Paris, he wrote home regularly to his mother, he sketched his nudes at the Académie Colarossi, and he drank wine in moderation. He was at that time considered by those who knew him as a bit reserved, verging on the asocial. He is noted to have commented, upon meeting Picasso who, at the time, was wearing his trademark workmen’s clothes, that even though the man was a genius that did not excuse his uncouth appearance.

In Paris, he discovered the work of Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin and, among the younger, more radical set, Henri Matisse and Picasso. Paul Cezanne in particular he pronounced “admirrrable, one of his favorite adjectives. Within a year of arriving in Paris, however, his demeanour and reputation had changed dramatically. He transformed himself from a dapper academician artist into a sort of prince of vagabonds.

The poet and journalist Louis Latourette, upon visiting the artist’s previously well-appointed studio after his transformation, discovered the place in upheaval, the Renaissance reproductions discarded from the walls, the plush drapes in disarray. Modigliani was already an alcoholic and a drug addict by this time, and his studio reflected this. Modigliani’s behaviour at this time sheds some light upon his developing style as an artist, in that the studio had become almost a sacrificial effigy for all that he resented about the academic art that had marked his life and his training up to that point.

Not only did he remove all the trappings of his bourgeois heritage from his studio, but he also set about destroying practically all of his own early work. He explained this extraordinary course of actions to his astonished neighbors thus: “Childish baubles, done when I was a dirty bourgeois…”

The motivation for this violent rejection of his earlier self is the subject of considerable speculation. From the time of his arrival in Paris, Modigliani consciously crafted a charade persona for himself and cultivated his reputation as a hopeless drunk and voracious drug user. His escalating intake of drugs and alcohol may have been a means by which Modigliani masked his tuberculosis from his acquaintances, few of whom knew of his condition. Tuberculosis – the leading cause of death in France by 1900 – was highly communicable, there was no cure, and those who had it were feared, ostracized, and pitied. Modigliani thrived on camaraderie and would not let himself be isolated as an invalid; he sought to suppress his coughing bouts and any other recognizable signs of the disease that was slowly consuming him. Modigliani used drink and drugs as palliatives to ease his physical pain, helping him to maintain a facade of vitality and allowing him to continue to create his art.

Modigliani’s use of drink and drugs intensified from about 1914 onward. After years of remission and recurrence, this was the period during which the symptoms of his tuberculosis worsened, signaling that the disease had reached an advanced stage.

He sought the company of artists such as Utrillo and Soutine, seeking acceptance and validation for his work from his colleagues. Modigliani’s behavior stood out even in these Bohemian surroundings: he carried on frequent affairs, drank heavily, and used absinthe and hashish. While drunk, he would sometimes strip himself naked at social gatherings. He became the epitome of the tragic artist, creating a posthumous legend almost as well known as that of Vincent van Gogh.

During the 1920s, in the wake of Modigliani’s career and spurred on by comments by André Salmon crediting hashish and absinthe with the genesis of Modigliani’s style, many hopefuls tried to emulate his “success” by embarking on a path of substance abuse and bohemian excess. Salmon claimed – erroneously – that whereas Modigliani was a totally pedestrian artist when sober,

“…from the day that he abandoned himself to certain forms of debauchery, an unexpected light came upon him, transforming his art. From that day on, he became one who must be counted among the masters of living art.”

In fact, art historians suggest that it is entirely possible that Modigliani would have achieved even greater artistic heights had he not been immured in, and destroyed by, his own self-indulgences.

During his early years in Paris, Modigliani worked at a furious pace. He was constantly sketching, making as many as a hundred drawings a day. However, many of his works were lost – destroyed by him as inferior, left behind in his frequent changes of address, or given to girlfriends who did not keep them.

He was first influenced by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, but around 1907 he became fascinated with the work of Paul Cézanne. Eventually he developed his own unique style, one that cannot be adequately categorized with those of other artists.

He met the first serious love of his life, Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, in 1910, when he was 26 years. They had studios in the same building, and although 21-year-old Anna was recently married, they began an affair. Anna was tall (as Modigliani was only 5 foot 5 inches) with dark hair (like Modigliani’s), pale skin and grey-green eyes, she embodied Modigliani’s aesthetic ideal and the pair became engrossed in each other. After a year, however, Anna returned to her husband.

Friends and influences

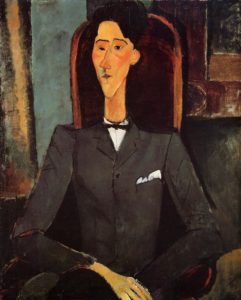

Modigliani painted a series of portraits of contemporary artists and friends in Montparnasse: Chaim Soutine, Moise Kisling, Pablo Picasso, Diego Rivera, Marc Chagall, Juan Gris, Max Jacob, Piet Mondrian, and Jean Cocteau, all sat for stylized renditions.

At the outset of World War I, Modigliani tried to enlist in the army but was refused because of his poor health.

In 1916, Modigliani befriended the Polish poet and art dealer Léopold Zborowski and his wife Anna. Zborowski became Modigliani’s primary art dealer and friend during the artist’s final years, helping him financially, and also organizing his show in Paris in 1917.

The 1917 Paris Show

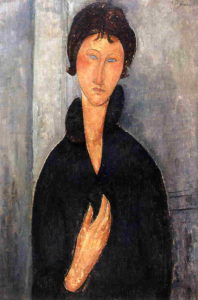

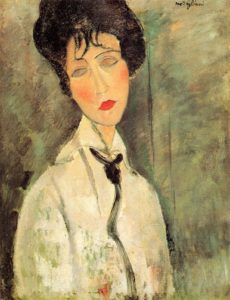

The several dozen nudes Modigliani painted between 1916 and 1919 constitute many of his best-known works. This series of nudes was commissioned by Modigliani’s dealer and friend Léopold Zborowski, who lent the artist use of his apartment, supplied models and painting materials, and paid him between fifteen and twenty francs each day for his work.

The paintings from this arrangement were thus different from his previous depictions of friends and lovers in that they were funded by Zborowski either for his own collection, as a favor to his friend, or with an eye to their “commercial potential”, rather than originating from the artist’s personal circle of acquaintances.

The Paris show of 1917 was Modigliani’s only solo exhibition during his life, and is “notorious” in modern art history for its sensational public reception and the attendant issues of obscenity. The show was closed by police on its opening day, but continued thereafter, most likely after the removal of paintings from the gallery’s street front window.

Nude Sitting on a Divan is one of a series of nudes painted by Modigliani in 1917 that created a sensation when exhibited in Paris that year. According to the catalogue description from the 2010 sale of the painting at Sotheby’s, seven nudes were exhibited in the 1917 show.

Jeanne Hébuterne

On a trip to Nice which had been conceived and organized by Zborowski, Modigliani, Foujita and other artists tried to sell their works to rich tourists. Modigliani managed to sell a few pictures, but only for a few francs each. Despite this, during this time he produced most of the paintings that later became his most popular and valued works.

During his lifetime, he sold a number of his works, but never for any great amount of money. What funds he did receive soon vanished for his habits.

During his lifetime, he sold a number of his works, but never for any great amount of money. What funds he did receive soon vanished for his habits.

In the spring of 1917, the Russian sculptor Chana Orloff introduced him to a beautiful 19-year-old art student named Jeanne Hébuterne[28] who had posed for Tsuguharu Foujita. From a conservative bourgeois background, Hébuterne was renounced by her devout Roman Catholic family for her liaison with the painter, whom they saw as little more than a debauched derelict. Despite her family’s objections, soon they were living together.

On December 3, 1917, Modigliani’s first one-man exhibition opened at the Berthe Weill Gallery. The chief of the Paris police was scandalized by Modigliani’s nudes and forced him to close the exhibition within a few hours after its opening.

After he and Hébuterne moved to Nice, she became pregnant, and on November 29, 1918, gave birth to a daughter whom they named Jeanne (1918-1984). In May 1919 he returned to Paris, where, with Hébuterne and their daughter, he rented an apartment in the rue de la Grande Chaumière.

When Modigliani died on January 24, 1920, Hébuterne was pregnant with their second child.

Death

Although he continued to paint, Modigliani’s health was deteriorating rapidly, and his alcohol-induced blackouts became more frequent.

In 1920, after not hearing from him for several days, his downstairs neighbor checked on the family and found Modigliani in bed delirious and holding onto Hébuterne, who was nearly nine months pregnant. They summoned a doctor, but little could be done because Modigliani was in the final stage of his disease, dying of tubercular meningitis.

Modigliani died on January 24, 1920. There was an enormous funeral, attended by many from the artistic communities in Montmartre and Montparnasse.

Hébuterne was taken to her parents’ home, where, inconsolable, she threw herself out of a fifth-floor window, a day after Modigliani’s death, killing herself and her unborn child. Modigliani was interred in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Hébuterne was buried at the Cimetière de Bagneux near Paris, and it was not until 1930 that her embittered family allowed her body to be moved to rest beside Modigliani. A single tombstone honors them both. His epitaph reads: “Struck down by Death at the moment of glory.” Hers reads: “Devoted companion to the extreme sacrifice.”

Modigliani, managing only one solo exhibition in his life and giving his work away in exchange for meals in restaurants, died penniless and destitute.

Legacy

The linear form of African sculpture and the depictive humanism of the figurative Renaissance painters informed his work. Working during that fertile period of “isms,” Cubism, Dadaism, Surrealism, Futurism, and Modigliani did not choose to be categorized within any of these prevailing, defining confines. He was unclassifiable, stubbornly insisting on his difference. He was an artist putting down paint on canvas creating works not to shock and outrage, but to say, “This is what I see.” More appreciated over the years by collectors than academicians and critics, Modigliani was indifferent to staking a claim for himself in the intellectual avant-garde of the art world. One can say he recognized the merit of Jean Cocteau’s proclamation: “Ne t’attardes pas avec l’avante garde” (“Don’t pay attention to the avant-garde”).

Since his death, Modigliani’s reputation has soared. Nine novels, a play, a documentary, and three feature films have been devoted to his life. Modigliani’s sister in Florence adopted their daughter, Jeanne (1918-1984). As an adult, she wrote a biography of her father titled Modigliani: Man and Myth.